andrew carnie

| home page | introduction | art works | a few words | research | recent work |

interview by jack chuter 2010

You started from a background of education in the fields of both science and art.

Yeah, it was a bit mixed really. I did an art O-Level because I was interested, and then I kind of shifted back into the sciences. So art was a strong interest but it wasn’t “happening”. I was doing things in the background that kind of grew and grew irrepressibly when I was at university. I started reading zoology. And then I couldn’t hold back really – I felt a strong urge that if I didn’t go for it at that point then I was never going to get a foothold. I became very attracted to make art and that was what I’d do in the holidays and any spare time I had. And then I broke away when I was at Durham University – I just left towards the end of the second year and decided that I had to do it now or never.

Your artistic work is largely based around science. Was it a conscious decision to fuse both science and art or was that something that just came naturally to you?

Well it didn’t happen for a long time. I left Durham in the late 70s, went to Goldsmiths and made different sorts of work. And that went all the way through until 1990 – so I’d spent all that time making work that was not science-based. I went through various stages – when I was at Goldsmiths I was a sort of “object maker”, then when I left Goldsmiths I went to the Royal College of Art and did painting. Then I started doing sculpture, and a lot of these were made from suitcases. People were jokingly saying, “you’re getting a bit obsessed with suitcases” so I felt I had to do something else. And so in the background I started making some photographic works around science issues and going back to my interests in that kind of world. That’s not to say that all of my other words were devoid of connection with nature, and the land and environment – works like “Patchwork”, “Hedge”, “Fossil”, “Pearl”…there was a lot that was quite organic. I think the changing point was around 1996. I was making a few black and white photographic pieces that are in the show – “Breath”, and “Whistle”. And then the photographic work started creeping up a bit, until I made Magic Forest in 2002. Then I stopped doing all of the other work. Up until that point I was still shifting back and forth – still doing a lot of computer-driven images up until the late 90s as computing and art were just fusing at that point. So I was doing a lot of work using the replication of photographic material as a form of sculpture almost. The computer gave the opportunity to use photographic ‘material’ over and over, so I had as much suitcase material as I could ever want.

Some of your pieces in “Dendritic Forms” exhibition are from 1994 and 1996, and then you’ve got works from this year or the year before. How have they all been united for “Dendritic Forms”?

In a sense that’s down to Robert Devcic who runs the gallery (GV Art). The slot for the show came up, and there was a bit of debate about what might show, as there was a notion that I might show earlier work – early paintings and things – and then there was this thought of “well why don’t we thematically it around “Magic Forest” and go back through all of the work and search through where the tree motif occurs – where the “Dendritic Forms” come in. It was always meant to be a show that was fairly straightforward to put together. “Magic Forest” had just been in the States, and a copy of that came back that was fairly new and in a good state, and all of the other photographic works were here in Winchester where I live, so it was a matter of sorting through those. But there were certain tree/root-shape pieces that we didn’t select because they were larger and slightly more inaccessible, that would have fitted the subject matter but weren’t accessible at that point. And there’s the up-to-date ones – there had been a period where I was doing a project around perception, and my motif for that was based around trees, so there was a lot of current work that fitted in as well.

You say that Robert took part in the selection process for the exhibition. How much were you involved in this, and are you happy with the selection on display?

Yeah, I’m very happy. I’ve worked in more “non-commercial” spaces over the years where I’ve had more control over what was put on, but in this instance I was very pleased that Robert came along with a very clear eye as to what he wanted. So basically, I presented things to him that I was happy to show and then he selected from that – so in a way, both bases were covered. There were a few pieces I made in acrylic boxes that got left out, but that was understandable in a way, as I don’t think they’re completely resolved. The images are, but the way the boxes are made and are hung isn’t. So I think he made a good call on that.

When you say that they’re “unresolved” – do you mean that in reference to the way they’re produced? Is there more to be done on them?

The actual images are all done – they’re all photographic prints, and there’s nothing on those I would go back and change. It’s just about how they’re presented and how they work as objects now. I’ve got a couple of issues about how they connect to the wall, and yeah…I’m still not comfortable with the final realisation of that. So they’re resolved in terms of content – just the hanging system is not working.

So presentation is an issue – obviously as an artist, you want your pieces presented in the optimum environment. In the case of something like “Magic Forest”, which is very dependent on the location in which it’s presented – is that often an issue?

Yeah, it can be. It’s toured around quite a lot since it was made. In terms of Robert and the space he runs, GV Art…it’s a moderate space in comparison with some of the big spaces it’s been shown in. What I try to do every time is to adjust the screen size so it works within that particular space. Ideally it’s shown as a bigger piece. I believe the screen size at GV Art is about 2.4 metres…well, really what I like to see it on is screens that are a minimum of 3 metres across, up to 5 metres. A couple of the shows I’ve done in the states – at Exit Art and the Williams College Museum of Art – would use much bigger screens. Another thing that happens that I don’t fully appreciate is that the smaller the space, the more light that gets scattered around. When “Magic Forest” works ideally is in a large, cavernous space where you don’t see the screens so much…the images float a lot more. When it was first shown at the science museum in London it was in a rather tight space, and it kept getting smaller as the other works were added into the show. It certainly didn’t work as well as it did in my studio in Hackney, as that was a big space and it really floated.

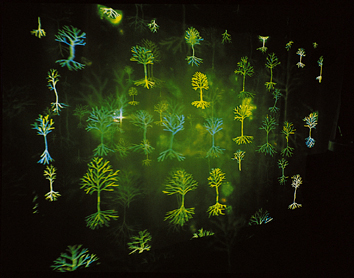

ANDREW CARNIE - "MAGIC FOREST"

Is that where a lot of your work is produced?

It has been in the past. When I moved away to work at the Winchester College of Art, I was still travelling back and forth to begin with from Hackney. But because of all the early testing I did, I have a fairly good idea about how effects will work, so quite often now I operate from a sort of glorified office. I mean I’m in there now…I’ve got some paintings on the go, some acrylic boxes on the floor, there’s a computer workstation and a couple of big monitors, and this is where I’ll work. And sometimes I might come up with a different screen configuration that usually works even though I haven’t ever tested it. Some of them are getting quite big now – the screens for “We Are Where We Are” are 6 metres by 6 metres, with 8 projectors standing 4 metres beyond that on every side, and I don’t have a test area for that. It needs a space some 16 meters by 16 meters. That’s always been quite nail biting really – going along and setting up quite complex things and just hoping it works, and then sitting down afterwards and being like “phew”. So that was true for “We Are Where We Are” and “Around Here”. It’s probably time that I spent a while in a larger space just testing things out again.

Has that always come through for you? Has there ever been a situation where you’ve set it up and it hasn’t been presented as you would have liked it to?

Well the major difficulty in these spaces tends to be what people understand by the term “blackout”. And that means to me pitch-black, and they always think they can get away with quite large gaps or entranceways that aren’t covered. That’s always been difficult to negotiate. And if you’re in a mixed exhibition with quite a lot of other people, you don’t want to be too pushy about getting technicians to do things and take things on, but it has been a difficulty on a number of occasions. But then what you have to do is throw a black cloth over their heads and get down really close to the projector and say “look – this is what it’s meant to look like”, and then they go “Oh right, that looks better. I see what you mean.” But other than that, I think it’s always worked pretty well once you’ve got the blackout. We’ve done it in some very large halls and small spaces and it’s been fine. I’ve had some technical problems in terms of projectors and dissolve units. That’s sometimes quite tricky when they don’t operate. The first time I went over to America, I took projectors and a dissolve unit from here (UK), and set the projectors to the American voltage unit and thought that would be fine. And after 5 minutes it just blew up the projectors basically. And that’s when I learnt about American equipment – I had to find some American projectors, go to an AV place, borrow some equipment and get it to work another way. Apparently it’s because the hertz – or frequency – isn’t the same, as the dissolve unit was made for this country and not America.

Would you say you’re now acquainted enough with the equipment so that you can realise these works more effectively?

Yeah, definitely. I went through a big learning curve in the beginning finding out about equipment, and in the end I started getting equipment made for me. I have these small slide dissolve units that don’t have any buttons on them, so that a curator could come into the space and turn on the projectors, and it would set all the slides back to zero and then work all day. That’s good stuff when that happens. Old fashioned projectors are difficult enough as it is – if the bulbs go…you need someone who knows what happens when the slides jam. I went through a few problems at the first show at the London science museum – stuff like contractors drilling holes in the security cases without taking the projectors out and getting sawdust in them. I guess reliability is a big thing. If you go into your exhibition and realise that it hasn’t been running properly for the last 6 hours or so then I guess it can be quite traumatic. Well I guess it’s the same with musicians. You have to know what equipment works and stick with the less fancy things if they’re going to be more consistent. The old Carousel projects like the Elmo ones made in Japan – they’re just workhorses really, just made to run and run. You have these exhibitions running all day long.

How long would you say is sufficient to see something like “Magic Forest” and absorb what’s going on?

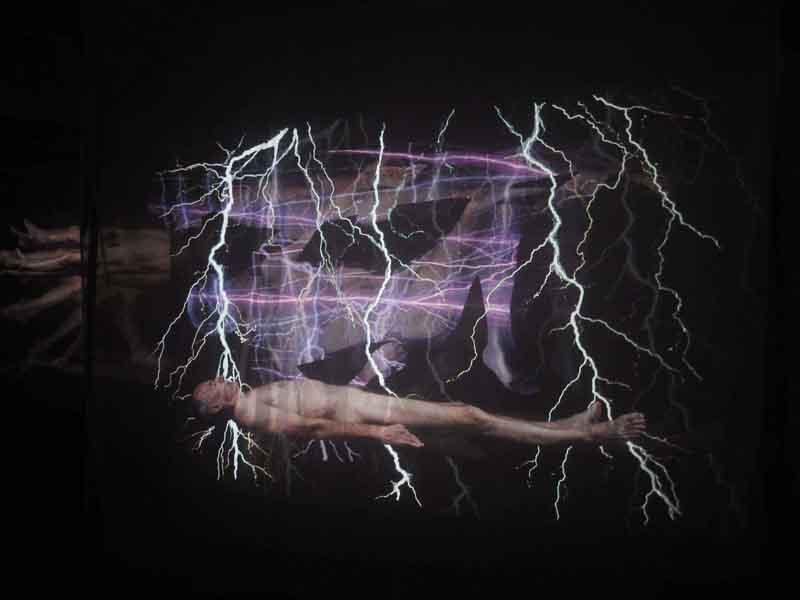

That’s a good question. It’s a difficult one. “Magic Forest” lasts about 20 minutes, and I think you need to sit in there for the duration but I do realise that people don’t. There’s an issue about how you manage this as an artist – could I make the pieces easier, shorter and quicker – but my tendency tends to be “no, this is what the work is, it lasts that long – if you catch it you’ll begin to see why it’s that long and get absorbed in it”. One of the things that I really like that doesn’t happen that often is when I show in a collection of rooms that all inter-relate, and then set two or three works up. I think that quite a lot of the works have quieter moments that are quite difficult to get through if you’re not in the mood in terms of viewer perseverance. If you set three works up all in different stages of development then you get caught up in one or the other. I did a show in Winchester at the Art and Mind festival, and I had three works set up in three separate rooms – a group of three people came up off the street and stayed two and three quarter hours, having just nipped into the building. And that was just a case of them watching one, and getting caught up by another one and realise that it had developed…I kind of like that idea of having more than one piece going. The piece “Seized: Out of This World” which is about Temploral Lobe Epilepsy is kind of based around that. One of the parts of the syndrome is that you get deja vu, so the piece plays with six projectors in sets of two, so there’s three different things going on, but they overlap quite considerably. They’re like the same chapters of a book but told slightly differently, and that allows for some of the slower passages – which I still think are really important – to be present. So you’ll see something in one of the other screens, and then go back and think, “oh, that’s the same as the other one…but no it’s not, as images are back to front or the head’s gone horizontal now or vertical”. So utilising that has been quite fun.

ANDREW CARNIE - "SEIZED: OUT OF THIS WORLD"

That’s brilliant. How long do you take over constructing these “narratives” for your work?

Quite a long time. When I was starting off… “Magic Forest” took about six months I think, and that was fairly heavy on the production and drawing side as all of the drawings are created on the computer in PhotoShop. But all of them are about six months…I mean “Seized: Out of This World” took a year from me starting it, as I was interviewing people for a while, talking to scientists, and I just had real problems with it. But I think it worked out really well. There were certain periods were I just didn’t know what was happening with it or where it was going, but it all seemed to come together in the end. So I usually count on it being at least three months and possibly more. But when I say six months, I mean working three or four days a week as there’ll be other things I have to do in the meantime, mainly teaching.

Back to “Dendritic Forms”. You’ve got a talk with scientist Richard Wingate coming up in August. How do hope that this will compliment the exhibition?

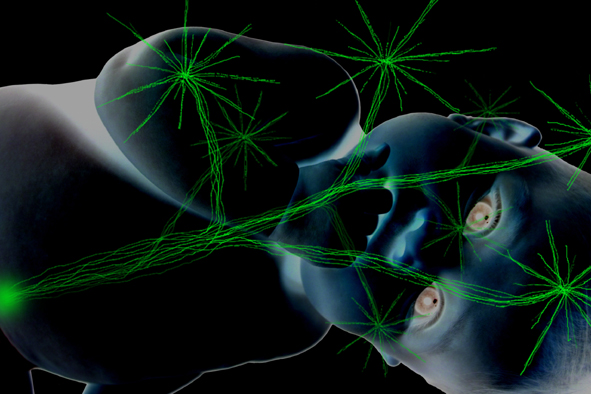

Richard and I have given talks together before. He’s the scientist that I talked to in getting the first bits of information for Magic Forest. We worked on one other piece together, “Complex Brain: Spreading Arbor” some two years after “Magic Forest”, various other little bits here and there, and then worked on several applications for money but never been successful with them. So we’ve touched base quite a lot over the years that I’ve known him, and that’s probably going on nine or ten years now. I think it’ll be a chance for people to question what the relationship to the science is and how it works – what the differences are in approaches and work. Richard has gone on over the years talking and being interested in that sort of interface, so it’s just a chance for people to unpick that a bit, and query and quiz it. There are many people who are sceptical about the area and sometimes I’m sceptical about that interaction. I think the difficulties are when you simply repeat the pretty pictures of science. I don’t want to be doing that – I want to make something that’s an artwork that’s in a different kind of space. The science that I’ve seen and explored are embedded in the work but they’re not they’re not always what the piece of work is about. Usually it falls into some other area, and I don’t even always know what that is. “Magic Forest” is a slide-dissolve work and being a series of slides in a carousel, it forms a continuous loop. It goes from start, blackness to a finish, blackness; it is a kind of life cycle of life. Growth, death, repetition. But that’s true in the brain as well, so that’s quite interesting.

ANDREW CARNIE/RICHARD WINGATE - "COMPLEX BRAIN: SPREADING ARBOUR"

So does this scepticism you occasionally have over the concepts in your art ever come through in your art?

Not as much as some artists I think. Some people are very critical of science practise. I’m just enthralled by some of the things that we know and how it’s been unpicked. I just think it’s extraordinary. I’ve started a project about ageing up in Newcastle recently, and I was there in the science labs last week. I know about DNA replication, but I never knew that we had these whole systems in our body – when our DNA gets broken, we have these enzymes that go around and patch it up and mend it. That’s kind of amazing. And just seeing some of the constructs that they understand. There’s a rich patina of proteins that are all working, and that all have jobs at a cellular level, and an atomic level too – some of the proteins are just small variations on each-other. And just about how when DNA is put into a cell, the cell will just replicate the protein and that protein will get to work – like when you put a green florescent protein in a cell, it will immediately start producing something florescent. And that’s just extraordinary.

You’re forever discovering and learning about stuff like this. Would you say that your artwork documents your continuation into science?

I don’t see it working quite like that. What I’m interested in is the ideas. Molecular chemistry at detailed levels – I can’t really make-work about as it’s just so particular, I just don’t know where I’d go with it. I’ve been to places where I’ve just walked away in the end and thought “given the choice, I’m not going to go to that lab, as it’s just so detailed – it’s amazing stuff, but I just don’t know what to do with it artistically”. That was certainly true for the Medical Research Council Centre in Bristol, for the Study Of The Synapse – I came away fascinated by the details they knew, the molecular structures of the synapses, the chemical formulae for the chemicals involved, but it was so detailed I couldn’t make work about it though. I can make work about the more generic ideas about movement and change but not about that. And it’s not the only kind of work I make anyhow – I make science pieces, but then I also make work about psychology or pieces that are just completely non-science. “451” is a piece about burning things, the end of everything…“Around Here” is about various different ideas thrown together – it’s a visual feast in a sense. There’s always these other works that I’ve done that I’ve made for quite different reasons. Everything strikes me as being grey rather than black and white – there’s a lot of merging of ideas, and it’s not clear that I’m completely engrossed in the science.

So science is just one factor that you find interesting enough to express artistically?

Yeah. For me it just gives us very interesting ways to reflect on who we are and what we are. Central to “Magic Forest” is that science was blowing away this concept that the brain is a static thing, it’s all wired like a computer, or washing machines or whatever – no, it’s an organic thing that’s altering all the time – laying down memories…they’re all processes, little signs of growth and change that are happening all the time. And I thought that was just fascinating really. I saw the exhibition a couple of week’s back, and “Magic Forest” is a great work to be immersed in. When it works properly you can sit through two or three cycles – I certainly have – in a mesmeric state. I quite like the meditational aspect. And coming back to your question about how long people need to see it for – in a way I was a bit defiant. I could have made it shorter and quicker. But in a way I think… scenes in cinema are quick and fast and over in a flash. I wanted a different experience in what is primarily an age of quick satisfaction. You can just sit down and ponder the work and absorb it.

andrew carnie cv.

andrew carnie satchi web site link

| about us | site map | privacy policy | finding the studio | catalogue | contact us | finding city road winchester |

© 2010 Carnie Art Services